The term language processing disorder is used frequently by speech-language pathologists, teachers, psychologists, parents, and others when discussing what appears to be language deficits that they observe in a particular student.

From the psychologist, they may see a pattern when testing where higher order language skills appear to be weaker than what IQ would predict. This may not be just on verbal comprehension tasks but may also be on visual task when the directions are overly complex. Therefore, the student has difficulty understanding what they are supposed to do on the visual task because the explanation and examples are too complicated from a language perspective.

For teachers, it may be that the student has difficulty following directions in the classroom. It may also be that student that always seems to be off topic, but when you do a classroom observation, it is obvious that the student is commenting on a previous topic because they needed more time to process information before they could respond. This appears off topic because the teacher has moved on to the next topic. They may also see that the student has difficulty organizing assignment, managing the time needed to complete the assignment, or disorganization when writing.

For parents, this may be that their child never seems to be on topic when talking to their friends. I had a parent relay a conversation that her child had with her friends while in her presence. The friend was talking about her vacation. and one small detail was about ice cream. The parent stated that her child discussed in detail her favorite ice cream although the conversation was supposed to be about the friend’s vacation.

For all, the student may appear to be disorganized when speaking, lack attention to a conversation, or classroom discussion, have difficulty in planning what they want to say, or be inflexible in their thinking and logic.

When a parent, teacher, psychologist, or another speech-language pathologist discusses concerns about a student and states that it must be language processing, I always have to ask questions such as, “What is your definition of language processing?” Because we do not have a diagnosis of language processing disorder either through the American Speech, Language, and Hearing Association (ASHA) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (2017). ASHA (2005) states under Central Auditory Processing Disorders the following information:

Richard's (2013) continuum of processing which is also included in ASHA’s (2005) position statement on Central Auditory Processing includes language processing (LP). This distinction between auditory processing and language processing provides direction for speech-language pathologists to determine what all is included in language processing. As Dr. Richard points out, language processing includes Heschl’s gyrus along the auditory pathway where meaning is attached to sound, Wernicke’s area for language comprehension, Broca’s area for expression, and the prefrontal and frontal cortex for planning and organizing which are executive functions.

Language processing can be defined as the integration of information at a rapid pace to develop appropriate listening and language skills including higher-order cognitive skills which include executive function and language, thus, it is how the brain creates language.

It is obvious to see the link between language processing and executive function in looking at the research.

Dawson and Guare (2004/2010/2018) provide a list of executive function skills that offers a roadmap to link executive functions with language processing. These are divided into skills needed for planning and achieving goals and skills needed for guiding behaviors. In their book, Executive Skills in Children and Adolescents: A Practical Guide To Assessment And Intervention, Third Edition they provide a questionnaire for parents/teachers and a teen version that can be used for assessment to determine strengths and weakness of each of the executive function areas (plus response inhibition and emotional control) listed below.

The following provides information on executive function skills and a crosswalk to what we may see from a language processing perspective. Each function is listed. Then, information given from a higher order language perspective. When we are designing our intervention, classroom accommodations and/or modifications, and ways to support parents at home, these executive function skills must be incorporated into our language goals.

The following executive function areas are needed for thinking and planning.

Thinking about what one wants to say and putting thoughts together in a logical sequential manner to determine the most essential information. Therapy suggestions will be given under the next executive function, organization.

Please see the next session for therapy ideas.

Organization goes hand in hand with planning and prioritizing. One must organize thoughts in a logical sequential manner. Students who demonstrate a lag in language may have difficulty organizing what is said to them into logical sequential chunks for processing a response.

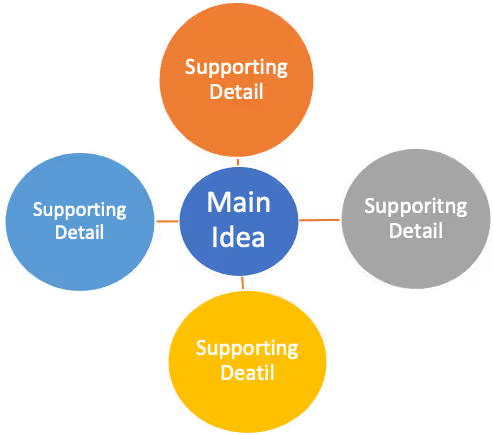

A visual graphic organizer such as a Mindmap would support a student in organizing thoughts and planning what they want to say. The goal is for the student to be able to visualize this organizer and better manage the chunks of information.

Determining speaking time after one plans and organizes thoughts.

Support the student in determining the main idea and the most important details so that when they begin speaking, these can be the focus.

Holding a conversation into memory to respond which if vital to overall language processing. If all the information cannot be held into working memory, information will be missing, and the student will have to fill in the gaps.

Students with working memory deficits will need accommodations and/or modifications in the classroom and at home. These may include written information in addition to auditory information. Previewing information that will be presented in class. This can either be competed in language therapy or the evening before it will be presented in class.

Holding information in mind while performing complex tasks. Ability to draw on past experiences to apply to situation at hand or project into the future. This includes the ability to add to and revise background knowledge based on current information.

Goals for therapy may need to include relational reasoning tasks such as determining similarities and differences, determining information that is contradictive to what they know and justifying a position that may not be their own.

The following executive function skills are usually associated with guiding behavior, but it is easy to see the role that they also play in language processing. There are two other executive function skills for guiding behavior that play more of a minor role in language processing and are not included here. These are response inhibition and emotional control.

Maintaining attention to plan and organize thoughts. Most importantly, it is the ability to stay tuned into conversations, discussions, lectures even when the language gets to be too much or too complex.

Visual reminders such as those listed under Working Memory are beneficial.

After planning and organizing one’s thoughts, the student then needs to begin speaking in a logical sequential manner.

Use visual graphic strategies such as a Mindmap to help the student organize their thoughts before they begin to speak.

Being able to think of more than one reason or way. Lack of flexibility leads to a my side bias which decreases the ability to revise one’s background knowledge.

Therapy should concentrate on justifying a position that may not be their own to support the student in revising their background knowledge to understand that there is more than one way to think about information.

Staying in a listening situation even when the processing becomes overwhelming

Supporting the aforementioned executive function skills will also support goal directed persistence. Helping a student organize language coming in, visual supports for working memory, and using visual graphic strategies will assist students to maintain presence when language becomes overwhelming.

Ability to stay on track when expressing oneself and make communication repairs as needed.

All the previous suggestions should support the student in developing self monitoring skills.

So, when a psychologist asks you to evaluate for language processing, or a teacher says that a student is not following directions in the classroom, so it must be language processing, we need to ask questions about language skills as well as executive function skills to determine if it is language processing. Language processing is more than morphology, phonology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. It is how the brain creates language. For intervention to yield effective results, we must include executive function skills in our therapy practices for language processing.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.). Central Auditory Processing Disorder. (Practice Portal). Retrieved January 31.2022 from www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Clinical-Topics/Central-Auditory-Processing-Disorder/

American Psychiatric Association. (2017). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: Dsm-5.

Ardila A. (2013). Development of metacognitive and emotional executive functions in children. Applied neuropsychology. Child, 2(2), 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622965.2013.748388

Dawson, P., & Guare, R. (2018). Executive skills in children and adolescents, third edition: A practical guide to assessment and Intervention. Guilford Publications.

Im-Bolter, N., Johnson, J., & Pascual-Leone, J. (2006). Processing limitations in children with specific language impairment: the role of executive function. Child development, 77(6), 1822–1841. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00976.x

Novoa, O. P., & Ardila, A. (1987). Linguistic abilities in patients with prefrontal damage. Brain and Language, 30(2), 206–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934X(87)90099-X

Richard, G. J. (2013). Language processing versus auditory processing. In D. Geffner & D. Ross-Swain (Eds.), Auditory processing disorders: Assessment, management, and treatment (pp. 283–299). Plural Publishing Inc.